https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/281237-overview

Rectal cancer is a disease in which cancer cells form in the tissues of the rectum; colorectal cancer occurs in the colon or rectum. Adenocarcinomas comprise the vast majority (98%) of colon and rectal cancers; more rare rectal cancers include lymphoma (1.3%), carcinoid (0.4%), and sarcoma (0.3%).

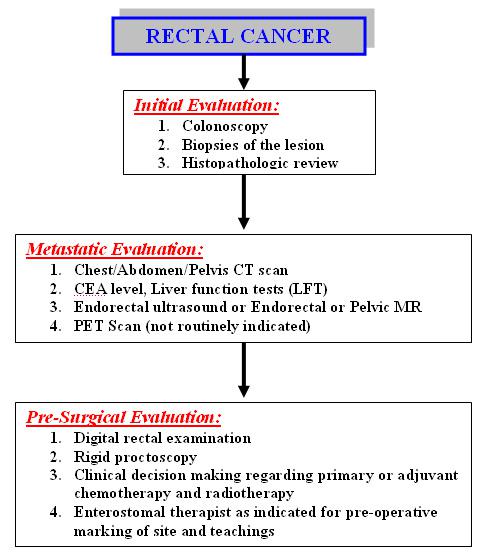

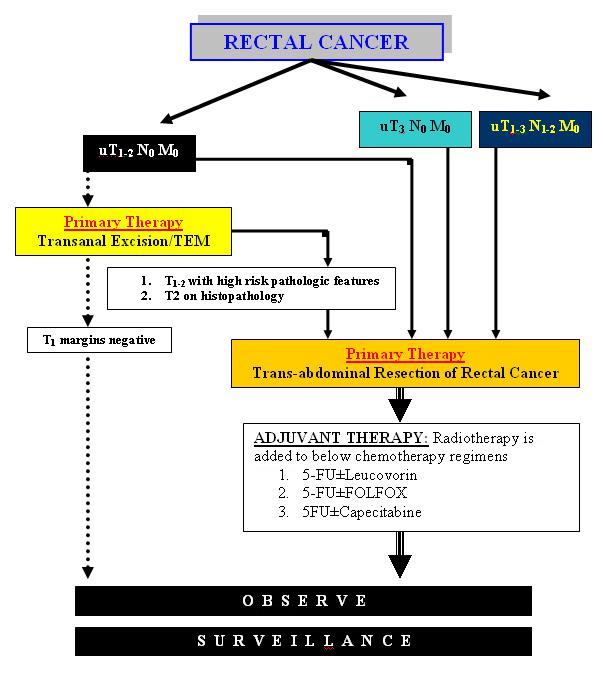

The incidence and epidemiology, etiology, pathogenesis, and screening recommendations are common to both colon cancer and rectal cancer. The image below depicts the staging and workup of rectal cancer.

Diagnostics. Staging and workup of rectal cancer patients.

Signs and symptoms

Bleeding is the most common symptom of rectal cancer, occurring in 60% of patients. However, many rectal cancers produce no symptoms and are discovered during digital or proctoscopic screening examinations.

Other signs and symptoms of rectal cancer may include the following:

Change in bowel habits (43%): Often in the form of diarrhea; the caliber of the stool may change; there may be a feeling of incomplete evacuation and tenesmus

Occult bleeding (26%): Detected via a fecal occult blood test (FOBT)

Abdominal pain (20%): May be colicky and accompanied by bloating

Back pain: Usually a late sign caused by a tumor invading or compressing nerve trunks

Urinary symptoms: May occur if a tumor invades or compresses the bladder or prostate

Malaise (9%)

Pelvic pain (5%): Late symptom, usually indicating nerve trunk involvement

Emergencies such as peritonitis from perforation (3%) or jaundice, which may occur with liver metastases (< 1%)

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Perform physical examination with specific attention to the size and location of the rectal tumor in addition to possible metastatic lesions, including enlarged lymph nodes or hepatomegaly. In addition, evaluate the remainder of the colon.

Examination includes the use of the following:

Digital rectal examination (DRE): The average finger can reach approximately 8 cm above the dentate line; rectal tumors can be assessed for size, ulceration, and presence of any pararectal lymph nodes, as well as fixation to surrounding structures (eg, sphincters, prostate, vagina, coccyx and sacrum); sphincter function can be assessed

Rigid proctoscopy: This examination helps to identify the exact location of the tumor in relation to the sphincter mechanism

Laboratory tests

Routine laboratory studies in patients with suspected rectal cancer include the following:

Complete blood count

Serum chemistries

Liver and renal function tests

Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) test

Histologic examination of tissue specimens

Screening tests may include the following:

Guaiac-based FOBT

Stool DNA screening (SDNA)

Fecal immunochemical test (FIT)

Rigid proctoscopy

Flexible sigmoidoscopy (FSIG)

Combined glucose-based FOBT and flexible sigmoidoscopy

Double-contrast barium enema (DCBE)

Computed tomography (CT) colonography

Fiberoptic flexible colonoscopy (FFC)

Imaging studies

If metastatic (local or systemic) rectal cancer is suspected, the following radiologic studies may be obtained:

CT scanning of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis

Endorectal ultrasonography

Endorectal or pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning: Not routinely indicated

See Workup for more detail.

Management

A multidisciplinary approach that includes colorectal surgery/surgical oncology, medical oncology, and radiation oncology is required for optimal treatment of patients with rectal cancer. Surgical technique, use of radiotherapy, and method of administering chemotherapy are important factors.

Strong considerations should be given to the intent of surgery, possible functional outcome, and preservation of anal continence and genitourinary functions. The first step involves achievement of cure, because the risk of pelvic recurrence is high in patients with rectal cancer, and locally recurrent rectal cancer has a poor prognosis.

Surgery

Radical resection of the rectum is the mainstay of therapy. The timing of surgical resection is dependent on the size, location, extent, and grade of the rectal carcinoma. Operative management of rectal cancer may include the following:

Transanal excision: For early-stage cancers in a select group of patients

Transanal endoscopic microsurgery: Form of local excision that uses a special operating proctoscope that distends the rectum with insufflated carbon dioxide and allows the passage of dissecting instruments

Endocavity radiotherapy: Delivered under sedation via a special proctoscope in the operating room

Sphincter-sparing procedures: Low anterior resection, coloanal anastomosis, abdominal perineal resection

Adjuvant medical management

Adjuvant medical therapy may include the following:

Adjuvant radiation therapy

Intraoperative radiation therapy

Adjuvant chemotherapy

Adjuvant chemoradiation therapy

Radioembolization

Pharmacotherapy

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend the use of as many chemotherapy drugs as possible to maximize the effect of adjuvant therapies for colon and rectal cancer.

The following agents may be used in the management of rectal cancer:

Antineoplastic agents (eg, fluorouracil, vincristine, leucovorin, irinotecan, oxaliplatin, cetuximab, bevacizumab, panitumumab)

Vaccines (eg, quadrivalent human papillomavirus [HPV] vaccine)